MIKE DONALDSON – A CAREER IN WATER JETTING (PART: 1)

Mike Donaldson, former Managing Director of SLD Pressure Jetting and a founder member of the Association of High Pressure Water Jetting Contractors, which became the WJA.

Mike took this picture of engineers examining a burst in a 48-inch gas main from Russia into Germany, which occurred during hydrostatic testing.

Don Gibb hydrostatic testing vehicles – which Mike designed and built before moving into high-pressure water jetting.

A high-pressure water jetting pump being fitted on a lorry chassis in the SLD Pressure Jetting yard.

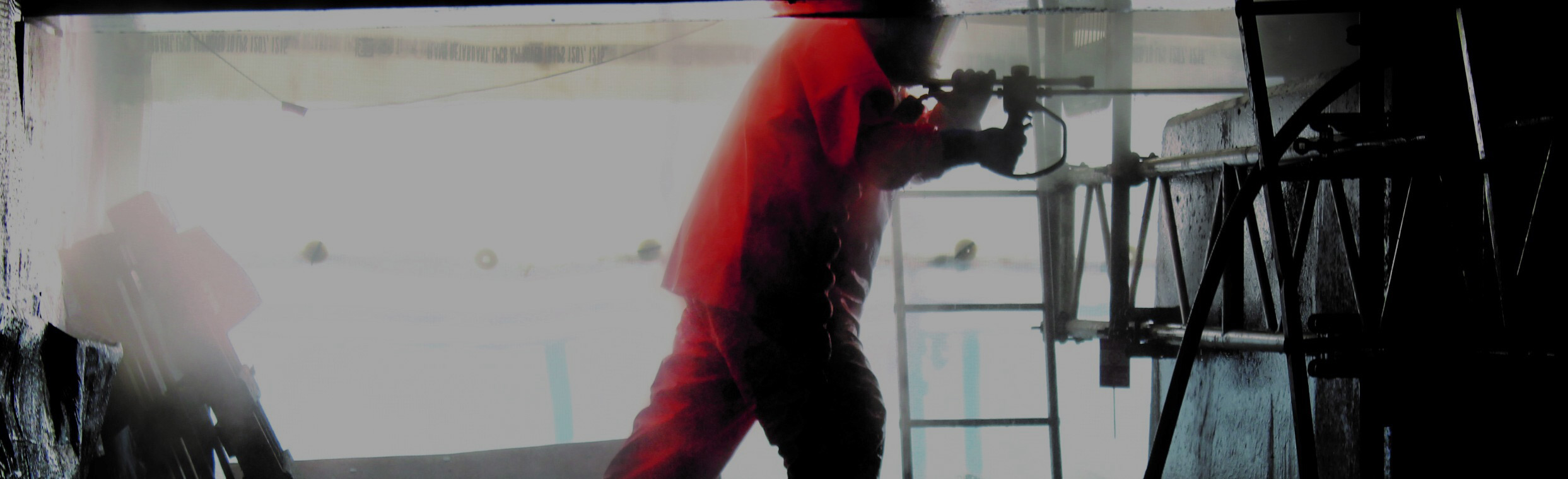

Under Mike’s leadership, SLD Pressure Jetting was one of the first companies to use water jetting to support motorway maintenance – here working on releasing deck bearings on the M6 through Birmingham.

SLD operatives using high pressure water jetting to remove concrete under the road deck in the Tyne Tunnel.

Mike inspects concrete hydrodemolition work in the Tyne Tunnel.

Mike, left, with Bruce Crompton, a director of Waterblast, while viewing damaged oil wells in Kuwait after the first Gulf War – they were certain water jetting could be used to help stop the fires and reopen the wells.

To mark this year’s WJA’s 40th anniversary, Mike Donaldson, one of the WJA’s founders, has agreed to share his thoughts on a highly successful water jetting career and how the WJA came to be formed.

In Part 1, Mike talks about how the rapid development of the water jetting industry in the UK, its challenges and successes.

In Part 2, he will recount how two key concerns paved the way for the WJA – safety and traffic police.

Starting out in business – from testing to jetting

In the early 1960s, Mike had been working as a plant manager during construction of the M1 in South Yorkshire when he was head-hunted by Taylor Woodrow to work on building an 8-inch ethylene pipe from ICI Wilton on Teesside to ICI Runcorn in Cheshire.

It was a huge project. The pipeline was 138 miles long. I also became responsible for hydrostatic testing of the pipe. Afterwards, Taylor Woodrow put me on standby to work on the site of the new Hartlepool nuclear power station. But because construction work hadn’t started, in 1966 I set up my own business, Don Gibb, and went into hydrostatic pipe testing.

“Town gas was being phased out. With North Sea gas coming on-stream, new pipes had to be laid because it was under higher pressure, which created demand for hydrostatic testing. I installed our pumps on chassis in custom-built truck bodies. We started doing a lot of work in Germany where they had larger diameter gas mains than in the UK, so there was more demand for the equipment we had.”

In 1972, Mike took the opportunity to sell Don Gibb to the Hanson Trust. The company was renamed SLD Pressure Jetting, with Mike as its managing director. As the new company name indicates, the company’s purpose had also changed.

“The Hanson Trust wasn’t interested in doing business in Europe and the testing equipment was too big for the UK market. So, I had the idea of changing the pumps’ performance and configuration so they could be used for high pressure water jetting instead.”

The pioneering years of water jetting

During the 1970s, water jetting technology evolved rapidly. British contractors were introducing new equipment, a lot of it from the USA, and pumps were becoming more and more powerful.

“We were struggling to keep up with the technology. We were constantly on the edge of what was possible. At the start, the highest pressures we were working with were 12,000psi. By the mid-1980s it was 15-20,000psi. By the 1990s, it was 35,000psi, and now it’s 40,000psi and over.

“At SLD we were trying to get more work in dockyards. We had to be pretty determined to make our case that water jetting would work. The ship maintenance and repair companies had established ways to clean ships’ hulls, mostly using tools like scrapers.

“They didn’t believe that a jet of water would remove the barnacles, rust and anti-fouling coatings. When we showed what we could do, even getting down to removing specific paint layers they were impressed. But it was a hard slog in some cases.”

During the late 1970s, more opportunities were emerging in the highway sector, the UK’s motorway network, rapidly expanded in the 1960s, threw up major maintenance challenges.

“Ten years after the first motorways were built, cracks started appearing, literally. The Ministry of Transport needed to start making urgent concrete repairs, starting with Spaghetti Junction in Birmingham. SLD was able to demonstrate that water jetting could be done overhead as well as horizontally, a significant step in terms of repairing underbridge supports.

“We were working for companies like WS Atkins and Maunsell. We were among the first to work on Spaghetti junction. The bridge bearings that should have lasted 20 years had worn out after 10 to 15 years. The conventional approach was to cut out them out with pneumatic chisels. We showed we could do it better with water jets.

“Each road deck was jacked up by 5mm, allowing traffic to continue to use the road, while we cut out the bearings and new ones were put in. Then the deck was dropped back down. SLD did the first 4,000 bearings to be changed.”

SLD hydrodemolition teams also helped carry out concrete repairs on the underside of road deck in the Tyne Tunnel for Wimpey. The company also cleaned glass-lined chemical vessels for ICI and Sterling Organics

“We’d often have to explain how water jetting worked. We’d be called in urgently to clean up a resin spill, and our clients couldn’t understand that we’d want to wait until the resin had gone off, because that’s the best time to removing it with high pressure jets.”

Emerging concerns about safety

Technology and safety systems were still primitive by modern standards, and a rising number of incidents focussed a spotlight on safety.

“We were using hydraulic hoses with the first fail-safe jetting guns in the UK. We were always trying to improve safety, but the technology was primitive by modern standards. If we didn’t get things exactly right, people could have been killed. There were a lot of accidents in the water jetting industry at the time. Especially with things going wrong with flexible hoses, which is why safety systems like the Chinese finger hose restraint was developed. Fixed installation systems didn’t have the same level of problems.

“In a lot of cases, there were body injuries caused when a hose burst and the operative lost control. Being struck by a jet of water was like being hit by a bullet and the water wasn’t clinically clean.”

The true extent of the seriousness of water jetting injuries was just starting to be understood.

“Medical professionals didn’t understand what they were dealing with when people turned up at hospital. That’s what led to the creation of the medical cards given to operatives so they had something with them that would explain the seriousness of injuries.”

As with all pioneering industries, water jetting had its share of irresponsible operators, says Mike.

“It was a business at the time where there was a cowboy element. Anyone could hire or buy the equipment and then undercut the prices of more established contractors. They didn’t know or didn’t care how to maintain equipment, and clients weren’t too worried as long as they were paying the cheapest price.

“We were concerned this was undermining confidence in safety across the industry. Even large organisations would take a chance with fly by night companies. The power generation sector was notorious for doing this. Water jetting companies would appear that you had never heard of before. Then after a few weeks they would be kicked off site and we would be invited to take over.”

New recruits and clients had to be constantly educated about the power of water jetting.

“For new employees, one of the first things we got them to do was to use a jetting gun to cut up a railway sleeper, just to simply prove that they should never put their finger in front of a jet. A lot of people don’t realise the energy in a water jet. When water is being forced through an orifice of 1mm diameter, its cutting power is huge. People have to be shown it to believe it.”

Fired up by Middle East opportunity

Opportunities were emerging to sell water jetting equipment and service in the Middle East, in the oil and drainage industries. A major war made the case for water jetting even more urgent.

“I had been doing a lot of business with Allan Earnshaw at Neolith Ltd before the first Gulf War in 1991 about opportunities to supply pumps and water jetting expertise to Kuwait to support their drainage industry.

“Then, after the war, my business contacts in Kuwait got back in touch and I went out with Allan and Bruce Crompton at Waterblast Ltd to see what opportunities there might be for us.

“As a result of the war, the drains had become full of debris, including ammunition, and it was thought water jetting would be a safe way to flush them out.

“We saw for ourselves the devastation caused by the war. There were burning oil wells everywhere, and we started to think how water jetting could be used to put out the fires and avert an environmental disaster.”

The famous American industrial fire fighter Red Adair had been contracted to cap the burning oil wells, but he did not appear to be using water jetting.

“Our idea was to lift a 10m-long pipe onto the burning well head, so the fire was moved to a greater height. Then we would use abrasive water jetting to create a clean cut at the bottom of the well head pipe. A new valve could then be lifted onto the pipe, allowing it to be closed off, extinguishing the fire.

“We were sure it would work but didn’t have the capacity to take advantage of the idea. We came back to the UK and told pump suppliers here about the opportunity. Red Adair was saying it would take three years to close off all the burning well-heads, but the task was completed in nine months, so perhaps water jetting played a part in speeding up the process. We certainly believed it would be beneficial at the time.”

In Part 2, Mike Donaldson talks about the specific stresses and strains that led directly to water jetting contractors realising it made sense to work together – and the significant benefits this has generates for water jetting customers.